CMU Rust Filterlab Reference: Double Hashing and SIMD

So, while I'm retired from running 98-008 Intro to Rustlang, I lurk in the instructors channel every now and then. I must credit my co-instructor Connor Tsui for making sure the future instructors have sufficient support, that whenever I get a notif in the instructors channel, there's a 99% chance that Connor has already answered it.

Today was like any other day, with Connor efficiently handling instructor questions.

Except this time, the question was about needing a reference solution for filterlab.

And I happened to have exactly that.

Disclaimer: If you are a current student, do NOT scroll down until you have given an honest attempt at filterlab. It's more interesting to go into it blind and not nearly as fun when you've been spoiled.

The complete code discussed in this post is available at rust-stuco/homeworks/week10/filterlab_ref_jess.

Origins of Filterlab

Filterlab was written in Fall 2024 by Connor, inspired by his bloom filter work at AWS Redshift. The assignment asks students to implement a bloom filter from scratch, a probabilistic data structure that efficiently tests set membership, with the caveat of possible false positives but never false negatives.

If you have questions about the lab or want to hear more about databases, Connor is the person to ask. He's currently a founding engineer at a databases startup and is always happy to talk about the course and real-world applications of these data structures.

While I'm at it, I suppose it wouldn't hurt to shout-out the co-founders of the course, Ben Owad and David Rudo, who literally wrote the course from scratch when they revived the second iteration with Connor, alongside the OGs who created the first iteration: Hazel and Cooper Pierce, who advised Ben, Connor, and David on building the second iteration.

We're all huge systems and security nerds.

The assignment is deliberately open-ended. Students are given only the interface specification and test cases, with the freedom to structure their implementation however they want. They must implement both a bit vector (the underlying storage) and the bloom filter itself, which uses multiple hash functions to set and check bits in the vector.

What makes this lab interesting is its real-world relevance. Bloom filters are commonly used as an in-memory filter in front of expensive operations like disk I/O or database queries. A false positive means wasted time doing expensive I/O.

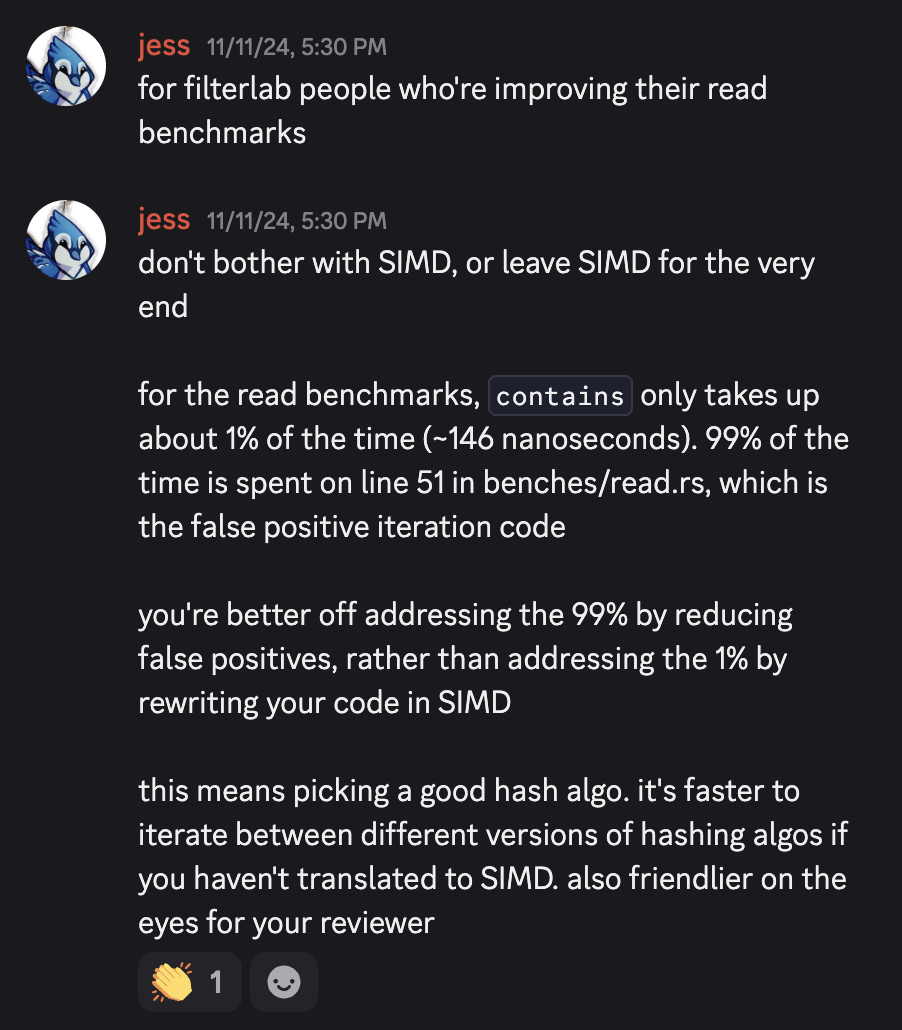

The 99% vs The 1%: What Actually Matters

When I profiled my filterlab implementation, I discovered something counterintuitive. Basically,

The

containsmethod only takes up about 1% of the benchmark time (~146 nanoseconds). 99% of the time is spent iterating through false positives in the test code.

To understand why, look at the read benchmark code:

c.bench_function("read", |b| {

b.iter(|| {

let elem = lookups[index % lookups.len()];

index += 1;

if bf.contains(black_box(&elem)) {

// This is the bottleneck

// The next line is very expensive if there was a false positive.

let found_index = list.iter().position(|&x| black_box(x) == black_box(elem));

black_box(found_index);

// 99% of time is spent here

}

})

});

When a false positive occurs, the benchmark has to linearly search through 1 million elements to verify whether the element actually exists. This simulates real-world usage where a bloom filter sits in front of an expensive operation, like disk I/O or database lookup.

No matter how fast you make bf.contains() with SIMD, a single false positive forces you to iterate through a million values. Going off of my measurements from Fall 2024,

bf.contains()took ~146 nanoseconds (the 1%)- Meanwhile, linear search on false positive took an order of ~microseconds through 1 million elements (the 99%)

Optimization Strategy

This leads to an important optimization principle: you're better off addressing the 99% by reducing false positives through better hashing algorithms, rather than addressing the 1% by rewriting your code in SIMD.

Practically speaking, this means you should

- Try different hashing algorithms first (faster to iterate, easier to reason about)

- Pick a good hash function that distributes uniformly

- Consider double-hashing on top of your chosen hash function to reduce computational overhead

- Leave SIMD optimization for last.

where the 99% comes from steps 1 and 2, 1% comes from steps 3 and 4.

That said, SIMD is still a valuable learning experience! Once you've nailed the fundamentals and want to squeeze out that extra performance, optimizing the 1% teaches you about modern CPU instruction sets (AVX2, AVX-512), vector operations and data parallelism, profiling and micro-optimization, and the gap between theoretical and practical performance.

So by all means, do both! Just in the right order.

Stop scrolling here! The above should give you pretty good guidelines on where to start.

Stop.

Stop.

Stop.

Stop.

Stop.

Google "hashing Rust" and "double hashing" and "SIMD" first.

You good?

Okay, here we go.

The 99%: Choosing a Hashing Algorithm

The first and most impactful optimization is picking a hash function that actually reduces false positives. This is where you'll get the biggest performance gains.

A good hash function for bloom filters should distribute uniformly across the bit vector and minimize collisions between elements.

I experimented with several hash functions available in Rust to find the hash function that gave me a low false positive rate for the benchmark's workload. Beyond just the hash function choice, I also tested different modulus operations, since this affects distribution and performance as well. To evaluate each one, I ran the read benchmark and measured how many lookups were false positives versus true negatives.

This experimentation is much faster than diving into SIMD and gives bigger performance gains. It's also easier to iterate: swapping hash functions is just a few lines of code. Once you commit to SIMD, changing your hash function means rewriting the entire vectorization.

The 1%, Part 1: Double Hashing

I could just tell you "try a different hash function," but let's be honest, neither you nor I came here for that. We're here for the SIMD intrinsics.

But first, let's talk about double hashing, because SIMD needs something specific to optimize.

When you have a good hash function, the next thing you can do is implement double hashing on top of it.

The reference solution provides a straightforward yet computationally expensive approach. For each element, it calls the hash function N times:

pub fn insert(&mut self, elem: &T) {

...

let mut hash = hasher.finish();

for _ in 0..self.num_hashes { // num_hashes is N

hash.hash(&mut hasher); // so we call this N times

hash = hasher.finish(); // and we call this N times

self.bitvector.set(hash as usize % size, true);

}

}

For num_hashes = N, we're calling hash.hash(&mut hasher) and hasher.finish() N times per operation. This computational cost adds up quickly.

The Double Hashing Improvement

Instead of hashing N times, we can hash just twice and generate the remaining hash values mathematically. This is the core insight of double hashing:

pub fn insert(&mut self, elem: &T) {

// Here, we only call the hash function twice

let (hash1, hash2) = self.hasher.get_hash_values(elem);

let bit_masks = self.bitvector.size() - 1;

for i in 0..self.num_hashes {

// ...and we generate the i-th hash mathematically

// zero calls to the hash function :)

let bit_index = self.hasher.get_ith_hash(i, hash1, hash2, bit_masks);

self.bitvector.set(bit_index, true);

}

}

The magic happens in get_ith_hash. Here's a simplified version of how it generates hash values:

fn get_ith_hash(&self, i: usize, hash1: u64, hash2: u64) -> usize {

let combined = hash1.wrapping_add(i.wrapping_mul(hash2));

combined as usize % self.num_bits

}

I actually iterated through several versions of get_ith_hash, of which you can view them in doublehasher.rs (source).

This formula hash1 + i * hash2 generates a sequence of hash values from just two base hashes. It's based on the well-studied technique of double hashing in hash tables, which provides good distribution properties while being computationally cheap.

This approach already gives significant speedup over calling the hash function N times, especially when N is large. But we can do even better...

The 1%, Part 2: SIMD

Okay, now for the fun part.

With my double-hashing implementation solid in doublehash.rs, I created a separate file doublehasher_x86_avx.rs(source) to explore SIMD optimizations.

I highly recommend you keep your SIMD implementation separate from your pre-SIMD implementation. It's faster to swap in different versions of hashing algos for the pre-SIMD version, and it's also friendlier on the eyes for your reviewer.

Our SIMD rewrite is targeted at a very, very specific part of our code, specifically the loop where we call get_ith_hash N times.

pub fn insert(&mut self, elem: &T) {

let (hash1, hash2) = self.hasher.get_hash_values(elem);

let bit_masks = self.bitvector.size() - 1;

// --BEGIN rewrite this using SIMD--

for i in 0..self.num_hashes {

let bit_index = self.hasher.get_ith_hash(i, hash1, hash2, bit_masks);

self.bitvector.set(bit_index, true);

}

// --END rewrite this using SIMD--

}

Since each hash calculation hash1 + i * hash2 is independent, this loop is a perfect candidate for SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) parallelization. SIMD allows us to compute multiple hash values simultaneously using vector instructions.

I'll revisit this section and write it in more detail later. Perhaps the irony is that in spite of contributing 1% of the performance, it already takes up >>1% of the blog post length.

For now, I'll leave you on this cliffhanger: